“Dear world, please help!” The heartrending plea of a daughter who has been searching in vain for her mother, folklorist Rahile Dawut, for the past three years.

“Dear world, please help!” The heartrending plea of a daughter who has been searching in vain for her mother, folklorist Rahile Dawut, for the past three years.

by Ruth Ingram

There is no end in sight.

Living with the agony of silence since the renowned Uyghur folklorist Rahile Dawut was snatched at Beijing airport in December 2017, her daughter Akida Pulat has left no stone unturned in her mission to find where in the murky labyrinthine tunnels of detention, so-called transformation through education camps, or extra-legal prison terms the CCP has buried her mother.

The black hole of silence has been deafening, and every plea for information from the Chinese government has been stonewalled.

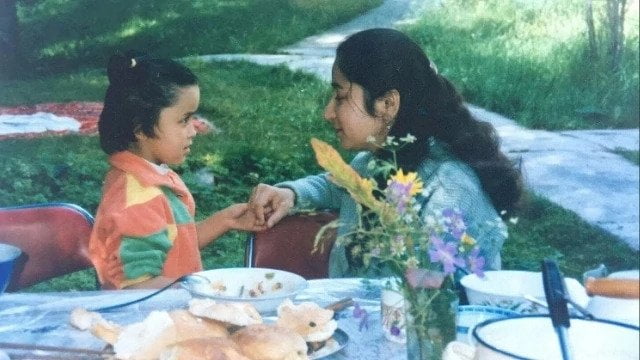

Akida’s life has been put on hold since her mother’s disappearance. The once happy-go-lucky twenty-something young woman, who enjoyed her career, the company of friends, movie nights and shopping, has become obsessed with the search. She came to the USA in 2015 for a Master of Science in Information Systems at the University of Washington. Her mother joined her for six months as a visiting scholar in 2016, and the last time they saw each other was at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport as the departure gates closed. “Neither of us expected that she would become one of the more than one million Uyghurs detained by the Chinese government,” Akida tells Bitter Winter ruefully.

Akida is one of tens of thousands of Uyghur exiles scattered throughout the world, who have been severed not only from their homeland, but also from their families. Which of them could have imagined that their visit to the West would be a one-way ticket, propelled alone or in small family groups into a future where going back was no option? The moment the new governor of Xinjiang province, Chen Quanguo, seized control of their destiny in August 2016, all contact with home was cut off. Those back in the homeland receiving a call from outside were summarily disappeared. If any dared to succumb to pressure and return, arrest at the airport was de rigueur.

There are those who have heard informally that relatives have been sent for “re-education,” or been victims of kangaroo courts and sentenced to long periods behind bars, for crimes such as “unusual” beards, long skirts, or the Skype app on their phones. Their exiled relatives might cynically be described as the lucky ones. At least, they have heard.

Others such as Akida, and relatives of the hundreds of academics, poets and intellectuals who have simply gone missing, live in the twilight abyss of unknowing. Their children, often sent to study abroad to widen their horizons and work for a better future for themselves and their people, are now alone, wrenched from the umbilical cord of financial and emotional support, left to fend for themselves.

Akida finds herself constantly rehearsing all the “what if’s” and “if only’s” of those who have suddenly lost a loved one.

She admits with shame, and mountains of regret now, that her interests and those of her mother’s rarely coincided. She was busy pursuing a career in technology that was light years removed from the daily lives of those whose folk tales, ballads, dialects, superstitions, and religious traditions intrigued and captivated Rahile. As a teenager, holidays spent in the depths of the countryside listening to the elders sharing memories and singing long forgotten songs were frustrating, even boring, she remembers. She could not wait to get back to “civilization” to gossip and shop with friends.

She is surprised at the changes in herself since this path was forced upon her.

These days she desperately tries to retrieve those precious memories and the days she spent with the simple villagers, endlessly generous, who showered hospitality upon them with a largesse they could barely afford. She is beginning to appreciate, not too late she hopes, the intensity of her mother’s love for Uyghur culture. But of course, it is too little too late now for her mother to benefit from this awakening camaraderie. Would that they could have shared together unearthing the precious cultural treasures scattered to the four winds of the deserts and mountains of her homeland. “Looking back, I wish she could have felt my support and companionship,” she says, hoping against hope for another chance.

She spoke to her mother via her website last year to wish her happy birthday, in the vain hope that somehow her message would get through.

Speaking on the video, she says, “Every day, I am being tortured with the thought of the uncertain fate that you and other innocent Uyghurs are facing, and the outrageous behavior of the Chinese government in response to the Uyghur people’s plight.”

As a young graduate with plans and hopes, in no hurry to put down roots and content to let the future take care of itself, her mother’s fate and that of millions of her people has thrown her into a turmoil of uncertainty, confusion and fear. Frantic for answers, the hunt for her mother and the crusade against the injustice against her people has consumed her. Her life and her destiny have been changed overnight. “I have become an activist. From morning to night, I think of nothing else. I will find my mother.”

Consumed by the cruelty meted out to her mother, at first, she tried to juggle a full-time job with activism, but it all became too much. She has abandoned her profession and is now working full time for the NGO Campaign For Uyghurs, directed by Rushan Abbas, whose sister was sentenced in March 2019 to 20 years in prison. Her mission now and for the foreseeable future is to raise awareness of the ongoing plight of the Uyghurs, and campaign for world governments to join them in the fight for justice.

As she walked and talked with her mother beside the lake near their rented home in 2016, she remembers begging her to let her stay for a while to accrue more work and life experience. Rahile reluctantly agreed. But now in her daydreaming about the future, she wonders whether she will ever be able to return. “Will I be able to spend the rest of my life near my mother? Will she be able to move to the suburbs after retirement to spend all day quietly reading and writing? Will she be able to help me raise the grandchild she longs for one day?”

“You always told me to be a good person, and I never forget that,” she says. “Happy birthday, mom. I love you. Please stay safe and mentally strong. I want to send beautiful gifts for your next birthday. I want to share every beautiful thing happening in my life with you. I trust God, and that day will come. At the end of this letter, I want to share with you a quote I recently read ‘Where there’s hope, there’s life.’ It fills us with fresh courage and makes us strong again. I love you and I miss you. Your loving daughter, Akida Pulat.”

Source: Bitter Winter